is changing the future for Northland families

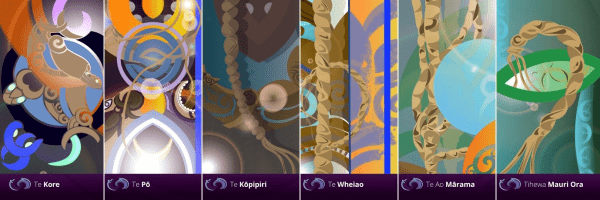

There are many signs that point to the special taonga status of wāhine hapū and wāhine Māori. We see it in the pūrākau of Papatūānuku and Ranginui, representative of wāhine and tāne (also the sky and earthly realms). In some narratives, whakapapa can be traced back through the women to Hineahuone, the first person formed from the clay of Papatūānuku by Tāne Mahuta. She is the direct connection to the atua. We find it in te reo Māori where the multidimensional meanings of words intrinsic to our identity bind them with the reproductive power of women. The word hapū or sub-tribe also has the meaning of pregnancy, whenua translates as land and is also the word for placenta, and whare tangata, the word for womb, also means house of humanity and is a celebration of women as the source of all life.

This view of wāhine hapū as taonga seems at odds with how some of our wāhine Māori experience our healthcare system. I’ve been told by the wāhine Māori in my life of how they had certain parenting or birthing practices imposed on them that don’t fit with their cultural values. They faced racial profiling and discrimination, mispronunciation of their names, and power imbalances between whānau and senior medical staff. Their cultural postpartum wishes were ignored, and often the time was not taken to even find out what those wishes were. But perhaps the biggest issue was not seeing other wāhine Māori in the system, especially as giving birth is such a vulnerable and intense time.

Link to videos and article: Embracing Māori birth traditions is changing the future for Northland families | The Spinoff